Coronavirus | Technology

Covid-19, technology and the food supply chain: Strained, but not broken

The lockdowns as a result of Covid-19 have put incredible pressure on the food supply chain, and experts are generally impressed with how it has coped with the system shock. But there are improvements to make if it is to maintain resilience, and data is key, as Lucy Ingham learns.

The Covid-19 pandemic has caused a shock to many systems and technologies upon which the modern world is built, not least the food supply chain.

As much of the world went into lockdown, the demands upon the food supply chain transformed almost overnight. With restaurants forced to close and many consumers switching to online shopping, demand for food by no means reduced, the critical supply points changed dramatically.

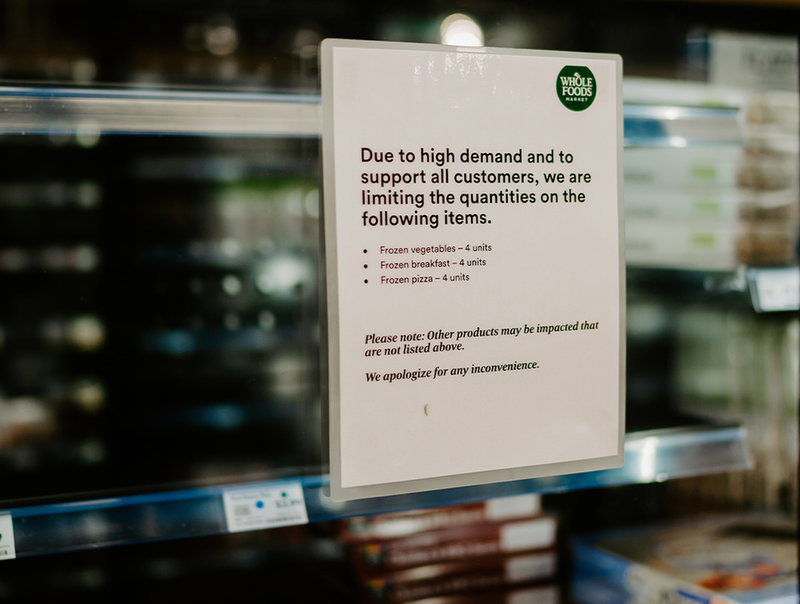

For many, the result was the much-publicised empty shelves in supermarkets, with commentators and consumers using such sights as evidence of a food supply chain in ruins.

However, many experts argue that this is not only the case, but that given the circumstances, the food supply chain and the technologies and companies that underpin it performed admirably.

Not out of the woods

Speaking at a talk entitled Industry 4.0 and the Great British Sandwich, hosted by the British government’s technology innovation agency Digital Catapult at online technology conference Virtual CogX, several experts from the industry made the case for why the food supply chain’s performance during the Covid-19 pandemic has so far been worthy of acclaim.

“I think it's done remarkably well,” says Simon Pearson, founding director of The Lincoln Institute of Agri-Food Technology at the University of Lincoln.

“Clearly, if you're in a supermarket and there's no food on the shelf, it's very distressing, but the additional volume of food that's been moved into the supply chain at incredibly high speed has been really very impressive. Millions of tonnes of food have been moved very quickly.”

“I have been impressed by how well the system has stood up; it has proven to be extremely resilient,” adds Julie Pierce, director of openness, data, digital and science at the Food Standards Agency.

“And some of the empty shelves may have been brought on by ourselves as in lockdown: we changed our behaviour. And by that I'm not talking about stockpiling, because I think the vast majority of people weren't stockpiling, but they may be doing a bit more home baking, so putting more pressure on certain food items.”

I think modern data, a more active, proactive predictive analytics is what is needed.

Despite being ready with praise for the food industry and the supply chain, Pearson stresses that when it comes to withstanding the system shock wrought by the coronavirus, “we’re not out of it yet”.

“It’s still early days. I think the demand-side has shown very large amounts of resilience. I think what we have not seen yet is the impacts on the supply side and the obvious risks of Covid transmission within food factories, on farms, that's an issue,” he says.

“And then you've got the longer-term downstream effects, in terms of planting new crops and all those sorts of things.”

Technology has the potential to assist with these challenges, particularly when it comes to enabling the agile responses required to support such issues, and those in the wider food supply chain.

However, some parts of the industry are better equipped to pivot as needed, which has not only created some of the more visible problems early in lockdown, but will continue to be a risk point in the event of future lockdowns and supply chain shocks.

“Where the supply chain didn't work so well was where some of it was already locked in,” says Pierce.

“So commodities were pre-determined: one of the classic examples was milk being predetermined to go to hospitality outlets, and trying to move into retail proved to be really, really hard.

“[But] many businesses have been very speedy and I've just been amazed seeing what people can do in a matter of a couple of weeks and equally surprised by some of those bigger legacy systems where they work fine when it's very, very predictable, but [struggle in] trying to change them [in response to] what's going on.

“I think modern data, a more active, proactive predictive analytics is what is needed.”

Technology, data and the food supply chain

Central to understanding how the food supply chain has performed is appreciating how it works as an ecosystem, and here technology plays a vital role.

“I look at the food system as a very advanced cyber-physical system,” says Pearson.

“And it's a combination of the amazing work done by millions of people; in the UK alone there's four and a half million people who make a living out of the food industry. And then all the digitals and the cyber systems, logistics systems which underpin it.

“They have worked, there's no doubt about it. They can always be better, and I think what we're understanding now is where it can be better.”

Core to this, according to Pierce, is understanding how much data is generated and exchanged in the creation of final consumer products. She gives the example of a typical supermarket sandwich, laying out the “hugely complex” net of data and interactions surrounding it on its journey from ingredients in fields to a final product on a shelf.

“So many different organisations, companies, individuals, countries have been involved in the production of all of the ingredients that made up that product that you eat for your lunch without really thinking,” she explains.

“Data flows through with that sandwich in relation to its safety; in relation to its authenticity in all of the ingredients; about allergens. All of that information needs to flow through every single ingredient that makes up that sandwich.”

This data comes from a myriad of sources, and is in some cases increasingly being collected using advanced technologies such as internet of things (IoT) sensors, while analytics platforms are being harnessed to identify and anticipate changes in demand, shortages and surpluses throughout the system.

This not only provides vital information for producers, suppliers and consumers, but also creates opportunities for efficiency gains across the system, saving money, reducing waste and lowering environmental impact.

However, the real potential for improvement to unlock these benefits, according to Pearson, doesn’t come from more sophisticated technologies, but from better approaches to how data is shared and managed to feed this system.

“It does work just generally well, but think about how it could work if it was undertaken in a more systematic, holistic way with more data being made available to everyone through that supply chain, getting those feedback loops understanding what is really going on,” she says.

“Anything that can be done to allow all of the actors involved with that, to just work better, I think produces a better quality product, not only the quality of the sandwich, that that you buy, and then eat, but all of the information that you need wrapped around that sandwich: you the consumer; you the retailer and everybody through the whole of that system.”

Sharing in the supply chain

Data is an incredible enabler for the food supply chain, but there are challenges in how it is acquired, implemented and shared within the food industry.

According to those on the panel, there is a need for data to be shared more freely across the ecosystem, so that the interplay between companies and systems with the food supply chain can be more effectively modelled and responded to, rather than data being siloed in discrete units where knock-on effects can be missed.

Sharing and collaboration data is actually the biggest barrier at the moment.

This issue of how to support data sharing within the industry is being explored by Pearson and his colleagues at The Lincoln Institute of Agri-Food Technology, and he recognises that there is considerable work to do.

“We're looking at the notion of data trusts and data governance, to try and underpin that, and the legal entities that are required to facilitate sharing,” he says.

“I actually think sharing and collaboration data is actually the biggest barrier at the moment. There's lots of data that should be shared that isn't. But we need a model; we need a safe place and a legal structure to enable that sharing.

“If we can unlock that, we’ll unlock a lot more value within the supply chain. Sharing doesn't mean giving for free, sharing means exchange, and possibly even financial reward for sharing, but that still needs a governance mechanism in a complex system.”

Honeypots and ecosystems

However, data trusts can bring their own challenges, with Scott Nelson, CEO and chairman of Sweetbridge, a company applying blockchain to supply chain and logistics collaboration, pointing to the cybersecurity risks they can pose.

“These are popular, but they have a weakness in that they create a honeypot,” he points out.

“And we've had so many cases of people hacking into systems historically and being able to take information, and the problem information is that once you possess it, you can copy it over the world anywhere you want to within moments.

“So it's not like stealing goods which have a physical limit to how easy it is to move. With data, once you get it, you can share anywhere and sell it many times.”

Nelson believes the solution instead lies in “other paradigms of technology” in the form of code that visits numerous sets of data held by different companies, rather than the data being collected and held in one place. Not only does this limit what can be exposed in a cyberattack, but it also gives more power to the data holders to limit what information is shared at what time.

“These enable you to ask questions without actually revealing any of the underlying information,” he says.

“Such as: I have 25 crates of lettuce that I can fulfil in an order without telling you that I actually have 25,000 cases, which maybe somebody doesn't really want to reveal, because that would create a situation where somebody could take advantage of that information.”

Most of all, however, he argues that solutions to these data challenges needed to focus not on economics, but on recognising that “these value chains are like complex ecosystems”.

“These complex ecosystems need to be treated as an entity that you’re part of, and that you get some value out of,” he says.

“In the existing environment, we compete firm-to-firm, and competing firm-to-firm in these complex ecosystems is actually not as profitable, long-term, as competing as ecosystems against other ecosystems.”