Regulation

Carbon emissions: a taxing problem for UK food

Food manufacturers, retailers, and governments are all announcing moves to achieve net-zero carbon emissions. With food making up a quarter of greenhouse-gas emissions, much hard work lies ahead. Could the fiscal system be part of the solution? David Green reports.

"H

ands off our sausages,” ran one headline, after a UK government memo proposed introducing a tax on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions that would apply across the economy, including agriculture and packaged foods.

The media backlash was unequivocal: a so-called ‘meat tax’ that would raise prices of beef, lamb, and dairy was the last thing farmers or consumers needed as the UK economy struggles to recover from the Covid-19 pandemic.

The impasse reflects a stark reality: developed economies must achieve net-zero carbon emissions by mid-century and to do so they must more comprehensively account for the environmental cost of carbon.

Addressing the carbon issue

“You want to encourage industry towards a more efficient way of producing food – it is putting a price on carbon because it has a cost,today and an even bigger one in the future,” says Myles McCarthy, director of the Carbon Trust.

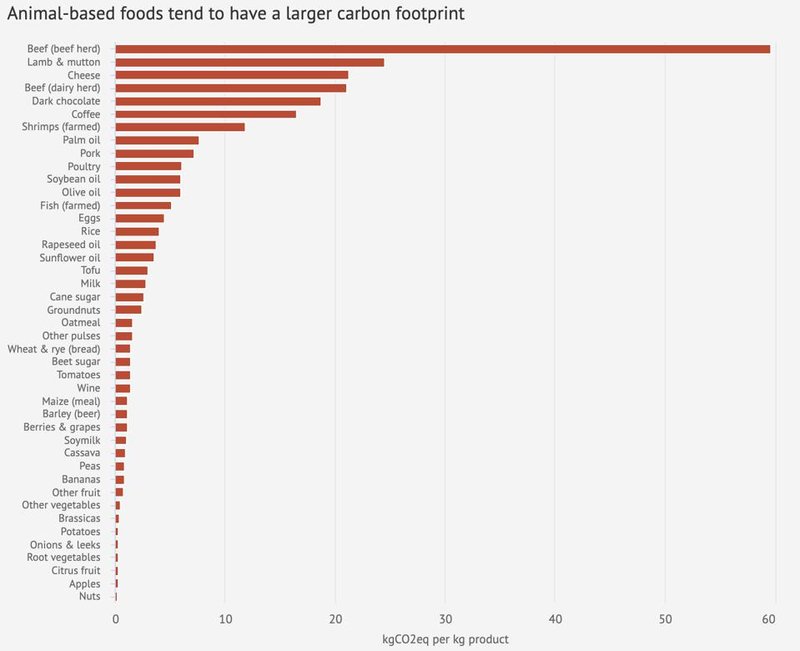

Food accounts for about a quarter of global GHG emissions, with livestock producing 7.1 gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent a year – about 15% of all human-induced emissions – according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization.

Methane, a potent GHG generated via feed digestion in ruminants, is the primary cause, supplemented by nitrous oxide released from fertilized soils and CO2 released as a result of land-use change and management.

Deforestation significantly raises the carbon footprint of grazed livestock – ensuring a carbon tax on food is de facto a tax on meat, lamb, and dairy.

Greenhouse gas emissions per kilogram for different food groups. Credit: Carbon Brief.

The challenge for policymakers is designing a system that both incentivises food producers to become more carbon-efficient and encourages consumers to opt for more sustainable diets.

As it stands, carbon emissions from energy-intensive industries, the power generation sector, and (to a limited extent) aviation, are capped and traded under the European Union (EU)’s Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS).

These account for about 40% of the bloc’s total greenhouse emissions and the ETS is widely accepted as having successfully weaned the EU off fossil fuels by incentivising the use of renewable alternatives.

For the time being, the UK has stepped back from the idea of using the tax system to incentivise decarbonisation as part of its own post-Brexit version of the ETS, due to be unveiled in May.

British icon, the Greggs sausage roll, pictured with Prime Minister Boris Johnson. The low-cost baked treat would no doubt have a price-hike following a carbon tax. Credit: Hannah Mckay/AFP via Getty Images

With Glasgow set to host the COP26 climate change summit in November, there was some expectation that the UK government would use its recent Budget to at least clarify its approach to carbon accounting.

“There was an opportunity in the last Budget to link super-deductions to carbon-friendly investments, but the government has not done that,” says Jason Collins, partner and head of litigation, regulatory and tax at the law firm Pinsent Masons. “HMRC has appointed a head of climate change tax policy, which is a good start, but [the] Treasury is the key player as they form tax policy and there is no direct equivalent just yet.”

That said, Collins believes that the UK government’s decision to raise corporation tax to 25% in 2023 provides the flexibility to incentivise companies that achieve net-zero with fiscal rewards.

“You can’t leave it to business and innovation, if we are serious about getting to net-zero, you need a tax system that is trying to achieve the same aims.”

Emissions accounting

Will Nicholson, project lead for investor metrics at UK think tank The Food Foundation, suggests structuring a tax on food is particularly tough because of poor emissions data.

“The lifecycle assessments have not been done on processed foods, one brand of biscuits, BBQ sauce, or cakes versus another,” says Nicholson. “The range of uncertainty is very high across meat products, especially when it comes to calculating emissions from ruminants.”

Tools for calculating on-farm emissions such as Cool Farm do exist, but rely to a certain extent on estimates.

In the absence of primary data, researchers have suggested using food category averages as a guideline for establishing a levy, but the problem here is that you disincentivise individual food producers to change.

In an example of the kind of innovative change that might be possible if the right incentives are introduced, scientists have found that adding a mix of garlic and citrus extract to dairy cow feed can reduce methane levels emitted in cow burps by up to 38%.

Other shifts include being more efficient in how we deal with waste from food.

“There are issues around the treatment of slurry and that’s an area of focus, along with land impacts and the best practices around fertilizer application and technology to optimise soil dynamics to absorb carbon emissions,” adds McCarthy.

When it comes to administration, levying a charge at the gate of slaughterhouses, dairies, and mills – in the same way that sin taxes such as those on tobacco and alcohol are charged – would be most straightforward.

There needs to be international coordination – if one country strikes out alone you are creating a competitive disadvantage because supply chains may move to countries that tolerate emissions.

But Nicholson suggests that a carbon tax would be less effective than adjusting land-use subsidies and legal frameworks as a means of nudging food producers to do the right thing in terms of, say, reforesting areas of farmland.

“If the government does apply a tax, it needs to work carefully with industry, because if business cases stack up, they will just do it. It needs to be something business will run with rather than mitigate.”

Collins points out any tax would need to ensure it does not distort competition by taxing producers in one jurisdiction but not in others, or double-taxing traded foods.

“There needs to be international coordination – if one country strikes out alone you are creating a competitive disadvantage because supply chains may move to countries that tolerate emissions.”

The EU is attempting to solve this by applying a tax to imported goods that have not had a carbon price applied to them. Initially, this will apply only to raw materials such as steel and cement but there is potential to expand to food and agricultural products later.

This would presumably cover food imported from the UK should it fail to follow suit, and from Mercosur, the South American trade bloc from which the EU sources three-quarters of its imported beef.

Moving up the packaged food supply chain, additional GHG emissions arise in the processing, refrigeration, packaging, storage, and transportation of food commodities, as well as the use of refrigerants in cold-chain logistics and retail displays.

The UK had already pioneered a mechanism that could put a carbon price on these processes within non-energy-intensive organisations such as supermarkets and hotels – the carbon reduction commitment (CRC).

Before it was abolished in 2019, the CRC asked businesses to monitor their CO2 emissions and purchase allowances to cover their costs.

“The CRC applied a tax of £12 per tonne of carbon,” says McCarthy. “Mechanisms for how companies could apply taxes to carbon emissions have been applied in the past and could be again in future.”

Under the EU ETS, carbon prices have since risen to more than £30 per tonne, while UK advocacy group The Zero Carbon Campaign (ZCC) is recommending an economy-wide average of about £75 per tonne is urgently required.

Corporate actions

In the meantime, The Carbon Trust is working with packaged-foods companies to cut their carbon footprint, focusing on end-of-life and recycled content in packaging, not least because it makes business sense to do so.

Investors are increasingly looking to pad their portfolios with companies demonstrating strong environmental, social, and governance (ESG) principles, which in turn is spurring consumer-facing brands and retailers to strive towards net-zero footprints along their supply chains.

For example, Unilever has announced it aims to achieve net-zero emissions from all products by 2039, while Tesco has pledged to become a zero-carbon business by 2050.

“As companies themselves do more, the government will recognise that there is more of an appetite for taxing emissions,” says Collins, adding that The Confederation of British Industry, the UK’s pan-industry business lobby group, is itself calling for financial incentives to go green.

UK industry body The Food and Drink Federation declined to comment on the idea of a carbon tax on food.

Consumer perspectives

From the consumer perspective, the literature is clear: we need to eat 35% less meat and dairy than we currently do by 2050, according to the Climate Change Committee’s Sixth Carbon Budget for the UK. The Climate Change Committee is an independent, statutory body established under the UK’s Climate Change Act 2008.

A 2010 paper in The American Journal of Public Health indicates the price elasticity of demand for meat is around -0.75, suggesting an increase in price of 10% leads to a decrease in quantity demanded of 7.5%.

The study suggests a tax would encourage behavioural change, but – as French President Emmanuel Macron found to his cost during the gilets jaunes protests against the cost of diesel fuel – raising taxes that fall disproportionately on low-income consumers carries high political risk.

“The opposition in France rose from a feeling of injustice – the average person has to go to work, and has no substitution for driving, whereas aviation fuel was not taxed,” says Xavier Irz, Professor of Agricultural Economics at the University of Helsinki.

“The lesson is that perceived fairness is huge, communication needs to be handled very carefully, and there needs to be transparency and a redistributive aspect.”

Mandatory carbon impact labelling on food products would inform sustainable consumer choices, and mean that producers would have to measure their impacts in a uniform way and be accountable for the results.

According to the ZCC, almost two-thirds of the UK public support a carbon tax on greenhouse gas polluters, with the proportion opposed falling from 19% to 6% if the idea of ringfencing the tax for carbon-friendly investments is made clear.

Irz suggests subsidies, or lower VAT rates, could be engineered to change the relative price of food across the basket, and that the proceeds from taxes on food with high emissions could be reinvested in climate-friendly innovation.

The idea of a tax on meat is gathering momentum in wealthy European countries such as Denmark, Sweden, and Germany, where advocates align the idea with the imposition of a sugar tax, as has been levied in countries such as the UK, Ireland, and Portugal.

In the UK, supporters of the idea suggest the time is not yet right to institute a carbon tax on food, not least because of the economic impacts of Covid-19.

“More importantly at this stage is the introduction of mandatory carbon impact labelling on food products,” says Laurence Bourton, a spokesman for the UK Health Alliance. “This would inform sustainable consumer choices, and mean that producers would have to measure their impacts in a uniform way and be accountable for the results.”