Interview

“We need to up our game on automation” – Danish Crown on the future of meat processing

Henry Mathieu speaks to Danish Crown’s Henrik Andersen about the future of robotics in the meat processing industry – and why the group is investing heavily.

Henrik Andersen, Danish Crown’s

Henrik Andersen, the vice president of engineering at European meat processing giant Danish Crown, is at the helm of implementing automation and robotics into the company’s operations.

Danish Crown recently announced a plan to boost earnings over the next two years through a multiple-faceted initiative, including improving efficiencies in its facilities through technology to cut production costs.

Just Food sat down with Andersen to discuss how automation will help a meat processing company, some of the key challenges it presents and the future of human jobs at the business.

Henry Mathieu: Danish Crown recently revealed a cost-savings plan with an aim to improve the company’s operational performance over the next couple of years. How big a role will investment in automation play in this plan?

Henrik Andersen: In Denmark today, we probably have more automated plants than any other countries in the world. We also have, by a margin, the highest salary costs. I think the hourly costs, compared to our plant in north Germany for instance, are twice as much as Germany, probably three times what they are in Spain. So, we have to offset that imbalance somehow. You can say we have traditionally been able to offset it by having had a high level of automation.

We’ve had in Denmark historically, as a large pork exporter, the benefit that we've been able to have a very high-quality carcass and sell it at an ideal price in a multitude of markets. What we’re seeing, of course, is that the world and our competitors are also becoming more and more automated, at least I’ll say on the ‘low hanging fruits’.

That means that we have to up our game a little bit and take it to “generation two” with what we will do in automation.

Henry Mathieu: Will your new plant in Manchester in the UK have a similar focus on automation as operations in Denmark?

Henrik Andersen: I usually split up the meat processing into what we call the primary production – which is basically where you get a live animal and you put a carcass into a chilled room. Then there is secondary production, which is when you basically take a carcass and put it into fresh meat.

And then we have the further processing, which is what we’ll be doing in Rochdale, in the new plant. We’re building a huge plant up by Manchester to process bacon. That process in Manchester will be extremely automated. In other words, a few people per tonne.

The most difficult thing is actually the secondary production, actually taking a half carcass and putting it into pieces of fresh meat. This is where most of the people are employed. It’s also where most of the effort will go into. The further processing is slicing, packaging and stuff like that, and it is actually a relatively automated process today.

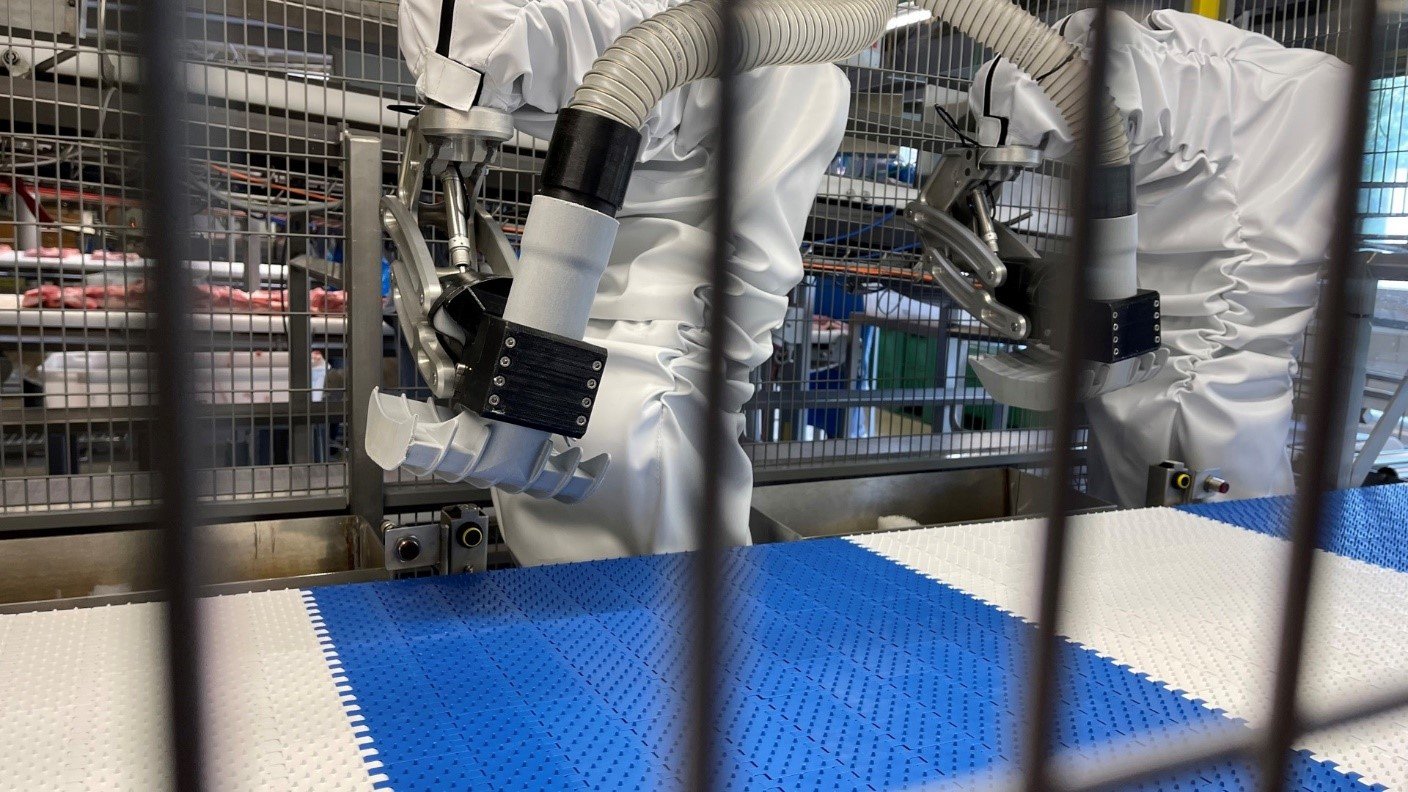

Credit: Danish Crown

Henry Mathieu: In December, Danish Crown announced it had allocated around 10% of its total investment budget of over DKr2.2bn ($320.3m) towards automation in production. How big a jump in budget is this towards robotics?

Henrik Andersen: I would say it’s at least doubling. Some of our reinvestments will embed automation also but what I think we define as automation is investments where the driver is not reinvestment of equipment we already have but where the driver is to convert manual labour to robotics.

Henry Mathieu: How far can automation go in the supply chain of meat processing companies? What are the main challenges that it presents?

Henrik Andersen: Automation in the meat industry is – if you compare it to many other industries – actually quite low. Particularly for meat, you have this problem that you have an extremely inhomogeneous raw material.

We will have to take out the, you can say, trivial jobs.

If you’re welding cars, I know that once you’ve programmed the robots, the next one million cars will be exactly the same. Whereas with pigs, there are one million individuals and so going from A to B is simple, but knowing where A and B is on a pig is not trivial. That is why it is difficult to automate compared to other industries.

You also have the problem that you’re working with fresh meat. You have to get it to the customers, and you have a continuous flow of things that you cannot pump into a tank or something like that. You have a continuous Source A conveyor that must run all the time.

So, these are some of the things that makes it difficult to automate. But, of course, if you are a little bit of a geek like me, it also makes it extremely interesting to automate because it is a challenge. The next two years and the years coming after that, we will have to up our game to automate further and to take out you can say the trivial jobs.

Henry Mathieu: What “trivial jobs” does the company plan to replace with automation?

Henrik Andersen: In an abattoir or meat plant, you have many operations which require a craft or a trade. Deboning is one, taking out a bone from ham and not leaving half the ham on the bone is a craft, it’s a trade. And it’s extremely difficult to do robotically because one cannot see and again you have this soft inhomogeneous product.

I think many of the things that we will work on is to automate many of the operations which are repetitive in nature. These are also the operations which our employees would least like to have. They also tend to introduce wear and tear on employees when you have these continuous, simple and uniform operations.

Where we are working on now is to have more or less an automated slaughter line. The process of slaughtering is, I would say, as automated as we can. We have one operation where we need to focus but we will focus on the automation of logistics, internal transportation and cutting. For the time being, you can probably just accept that deboning is a trade, which will be too difficult to automate in this coming wave.

We have these criteria that once you automate, there is no physical room for the operator because the robot stands where they're supposed to be standing. Once we go that way, we need to have an uptime above 99.5% because we have a number of operations which do not run in parallel but in sequence. It has to be extremely robust, and it has to be reliable.

The goal is that we can take out a lot of salary costs because that will put Denmark back in an even playing field, so to say.

Henry Mathieu: Could you see a time when even the intricate jobs like deboning will be done by automated technology?

Henrik Andersen: I will say that we think eventually, in a third wave, we’ll get to that. But the plans we have for the coming two years will focus on internal transportation, logistics and the handling of the products through our plants. So, it’s not impossible but it is a mountain to climb.

Henry Mathieu: What does your investment in automation mean for human jobs? To what extent will Danish Crown redeploy human staff in other roles?

Henrik Andersen: In Denmark, a dual strategy was introduced. One was to automate to take out costs and the other one was to increase the valorisation of what we do. That will mean that we will require people to do more for the processing side.

We will use people to create value rather than pushing meat around.

The way I see it is that if we don't do anything, we will probably need another 1,000 people, which we are already having a difficult time to get. I think it’s more that the people that we have employed today and our level of employment will stay but we will just use them for things that create value, rather than using them for, you know, pushing meat around.

Henry Mathieu: After a fairly lengthy run of job cuts and consolidation in recent months, will the introduction of automation be an easy transition?

Henrik Andersen: I’ve always been told that you’re not allowed to say something will be easy, particularly things you don’t have to do yourself. I think my own experience is that usually you very quickly get to a point where you have something that almost works. Then it’s a logarithmic scale getting it from working 95% of the time to 99.5% of time. That’s where it gets tricky.

I think we will probably tend to look more at ease of implementation. We will try and evaluate things that we think we can implement easily and quickly but which would not have the same economic impact as a ‘Big Bang’ would have. I think we will probably try and balance it a little more to the ease of implementation.

Henry Mathieu: What specific technology innovation does the company see a future in? What emerging tech could support these efforts?

Henrik Andersen: I think it would be more of an incremental development in the sense that I think the big change which has happened in the last five or ten years is computation has become cheaper and available. Technology and costs have made things available that was not available to us ten years ago [which] will drive an incremental innovation.

The fact that computation and vision technology has become so much cheaper and more readily available means that if you develop an application – for instance as we are doing now to track cuts of meat through a plant by algorithms, similar to what you know from facial recognition, to have traceability – once you've developed software, which is not trivial, replicating cameras is not an issue or computation is not an issue. That would have been an impossible cost to carry ten years ago.

Henry Mathieu: Can you see more meat companies around the world implementing automation in years to come?

Henrik Andersen: I think so. If the US is included for instance, the issue is not just what you pay for people, it’s actually getting them. You have the same problem in the UK: for many meat plants, it’s just difficult to get people so I think that they will do so.

They will not have the same return on investment that Danish Crown will because they don’t have the same salary costs. But they have the same issue that, regardless of what they pay, they’re not getting the people and certainly not the quality of people that they would like. So, I think most other companies and countries will follow suit.